|

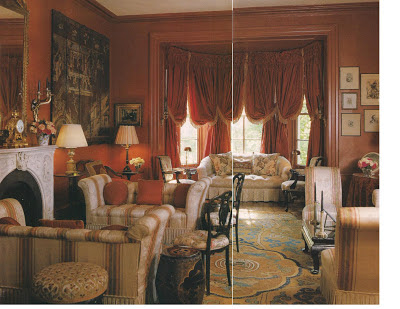

A Kips Bay Show House room by Robert K. Lewis

featured in an ad for F.J. Hakimian.

Architectural Digest, January 1990. |

In the days prior to internet exposure, decorator showhouse rooms were often an ephemeral commodity. Although a popular venue such as the

Kips Bay Decorator Show House in Manhattan would have several thousand visitors a day during the 3 to 4 weeks duration, a photo record of the rooms was not guaranteed to be otherwise circulated. Sometimes, a newspaper would photograph a room or two, but that usually would not extend to out-of-town editions. In the 1990s, vendors who had supplied their products for these rooms might place a glossy advertisement in a national magazine, however, that featured the room and its designer. The rug vendors were particularly helpful in promoting these showhouse rooms that might otherwise have not been seen across the country. One of most appreciated series of these advertisements were those done by the firm

F.J. Hakimian who headlined their ads with "Who chose the Hakimian?".

|

The Kips Bay Show House room by Juan Pablo Molyeux

also featured a ceiling commissioned from

Anne Harris Painting Studio loosely based on

Michelangelo's "Last Judgement"

that depicted the decorator's face on an angel. |

Typically, the Kips Bay Decorator Show House is located in an Upper East Side townhouse that is on the market for sale. (There have been instances, however, that such a property was not available). Usually there are at least a few rooms that already have architectural interest, but the others depend entirely on the décor for success. In any case, the foundation of any decorating scheme can always benefit from a terrific floor covering. Both

Robert K. Lewis and

Juan Pablo Molyneux benefited from their rooms have good 'bones' as well.

|

A Kips Bay Show House room by Mario Buatta

featured in an ad for Stark Carpet.

Architectural Digest, June 1991. |

Mario Buatta does his best work when he is his own client; his show house rooms are never a disappointment, and often the most memorable of the year. This room, pictured, also benefited from good, existing architectural detailing, but the real spark came from the talent of the decorator, putting all the furnishings together to create an attractive room. Here

Stark Carpet was the patron who featured the room in an advertisement. First with the addition of Old World Weavers fabrics, and now including Lelievre, Fonthill and Grey Watkins fabrics among others, the conglomerate known as Stark has become an even more prestigious To-The-Trade source, and promoter of show house designers.

|

A Kips Bay Show House room by Arthur E. Smith

featured in an ad for Stark Carpet.

Architectural Digest, November 1992. |

The room decorated by

Arthur E. Smith was in the same 1992 show house at 32 East 70th Street, New York City, as Molyneux's drawing room, but located on the fifth floor. A former protégé and business partner of legendary decorator Billy Baldwin who took over the office at the elder's retirement, only the use of sisal and kraft paper lampshades give a nod to his mentor. The late Mr. Smith, who also had an especially stylish antiques shop, was a well-respected talent in the NY area, but not particularly well known across the country (until his connection with gallery owner and accused killer Andrew Crispo was publicized).

|

A Kips Bay Show House room by Michael LaRocca

featured in an ad for F.J. Hakimian.

Architectural Digest, June 1993. |

A gothic revival library was decorated by

Michael LaRocca for the 1991 Kips Bay Show House at 121 East 73rd Street. The 1908 Federal Revival townhouse is located across the street from a John Tackett Design project at

128 East 73rd Street which held his field office for almost two years, coincidently, so this writer was very familiar with the house. (Additionally, assistance was provided to Mariette Himes Gomez who decorated the dining room for the same show house: a photo from a previous post may be seen

here.)

|

A Kips Bay Show House room by Justin Baxter

featured in an ad for Stark.

Architectural Digest, December, 1993. |

Despite the prestigious neighborhood, the 1993 Kips Bay Show House at 813 Park Avenue was in an awful apartment building consisting of a maze of rooms. The renovated spaces were all poorly proportioned and some had ceilings less than eight feet high.

Justin Baxter had one of these less-than-desirable rooms, but did an admirable job of pulling it together with the use of striped wallpaper and mirrors.

|

A room by Bennet & Judie Weinstock

featured in an ad for Stark.

Architectural Digest, April 1994. |

Based in Philadelphia, the husband-wife team of

Bennet & Judie Weinstock have been regular participants in the Kips Bay Decorator Show Houses over the years. This writer does not happen to remember this particular room, however, although it is assumed to have been a show house presentation.

|

A Kips Bay Show House room by Dennis Rolland

featured in an ad for Stark.

Architectural Digest, September 1996. |

This sitting room by

Dennis Rolland was remembered, however, and thought to have been featured in the 1994 Kips Bay Show House which was a double Georgian Revival townhouse designed by architect Charles Platt for Sara Delano Roosevelt and built 1907-08. In addition to the large red-pencil drawings that decorated the room, another notable feature was the soft gray ceiling which was reportedly colored with graphite.

|

A Kips Bay Show House room by Kenneth Alpert

featured in an ad for Stark.

Architectural Digest, March 1997. |

The sitting room by

Kenneth Alpert is another that, sadly, this writer cannot identify by year or address. But it featured a whole range of Stark products, most notably the popular carpet pattern of leopard spots and roses designed by Mrs. Stark, herself.

|

A Kips Bay Show House room by Scott Salvator

featured in an ad for Stark.

Southern Accents, March/April 2001. |

Scott Salvator is another Kips Bay regular and this writer is not sure of the date or address of this decorator show house. Notably, Mr. Salvator has also designed showrooms and offices for the Stark Carpet group.

A note of appreciation goes to both Hakimian and Stark for showcasing these interesting rooms and their designers in their advertisements over the years.